Can Git back a REST API? (Part 1 - the naive approach)

Git is basically a fancy file store with history, so can it be applied to use cases other than source control? Come with me as I try to repurpose Git into a backing store for a simple REST API

Git is great for storing code, and maybe the occasional image or two. It also makes it easy for teams to collaborate and deal with fine-grained changes. But could it be used as a more arbitrary data store? Can we force the square peg of Git into the round hole of a REST backing store?

As of right now, I’m not entirely sure! But come with me on this series of posts and we might find out.

There are a few APIs that might seem like precedent, such as the GitHub API. This gives REST access to repo metadata and even contents, but who knows what additional moving pieces there are helping power it? I’ll be looking at generic Git servers, using the standard protocols, no caching, no extra layers.

I’ll be building out a REST server using Git as a backing store, and comparing it to other storage options like S3 (or similar object storage services), the filesystem or a database. I’ll be working in Go, since it’s what I’m most familiar with, the standard library makes it straightforward to create an HTTP server, and I know of some libraries for interacting with Git and other storage.

I’ve set up a repo for the project at https://github.com/theothertomelliott/git-backed-rest.

Fundamental limitations

We can identify some limitations of Git going in. Since a Git repo stores the full history of a repo, size could become a concern over time (assuming we don’t do surgery on the commit history to clean up). Very large repos can suffer from performance problems, and GitHub recommends you keep total repo size below 5GB. In my experience, self-hosted Git servers can tolerate quite a bit more than that, but plenty of companies have bragged about databases getting into the terabytes, so eventually Git is sure to struggle to keep up.

Git is also designed with text in mind, so can have issues with binary or particularly large files. Git LFS exists for exactly this reason, and 100MB is a typical limit on file size.

I may try to work around these eventually, but for now, I’ll focus on discovering the unexpected, and building a small proof-of-concept that could be viable for low-intensity use cases.

The API

At its most basic a REST API allows you to manage resources with HTTP verbs, so I did just that.

To keep things simple, I’m building an API that interacts with byte slices at arbitrary paths using the following verbs:

GET

POST

PUT

DELETE

Note that PATCH and OPTIONS are out of scope since they require more complex interactions with resources and their metadata.

Example Usage

You could manage a user profile stored as JSON:

# Create a new user profile

POST /users/alice/profile

Content-Type: application/json

{”name”: “Alice Smith”, “email”: “alice@example.com”, “role”: “developer”}

→ 201 Created

# Retrieve the profile

GET /users/alice/profile

→ 200 OK

→ {”name”: “Alice Smith”, “email”: “alice@example.com”, “role”: “developer”}

# Update the profile

PUT /users/alice/profile

Content-Type: application/json

{”name”: “Alice Smith”, “email”: “alice@newdomain.com”, “role”: “senior developer”}

→ 204 No Content

# Delete the profile

DELETE /users/alice/profile

→ 204 No ContentThe path structure is arbitrary - you could use /api/v1/organizations/acme/projects/website/config.json or any other hierarchical structure that suits your needs.

This provides a very generic API that could be layered under middleware to provide more focused APIs for specific use cases.

A Naive Git Implementation

As a minimal-effort starting point, I set up a backend for the API using the Git CLI directly, specifically using the porcelain commands that most of us developers use every day.

A remote repo is treated as the source of truth, and a local copy is created to work against (using git clone). To ensure that you are always working with up-to-date content, every operation starts with a git pull.

Once content has been updated locally, the remote is updated with calls to git add, git commit and git push.

This approach will clearly have a few shortcomings, not least of all concurrency. With a pull, writing of files, an add, a commit and a push involved in updating content, the operation is most definitely not atomic. A race condition between two updates would most likely manifest as a non-fast-forward error. This initial implementation doesn’t attempt to do any kind of recovery in this case, so it would also leave the failed copy of the repo in a bad state, frozen at the point of the failure.

So while this implementation is naive to the point of being unusable, it can tell us a little about the performance characteristics of Git, so we I make some better decisions about the next iteration.

How does it perform?

To compare this Git backend with something mildly realistic, I also wrote an S3-compatible object storage backend (or to be totally transparent, I used Crush with Anthropic models to write it). I then set up integration tests using GitHub for Git and Cloudflare’s R2 for an object store.

These tests included a cycle that ran GET against an empty repo (to check for the expected 404), POST to create a resource, and GET to check the resource was written correctly. This provided a minimal set of steps that would be easy to compare.

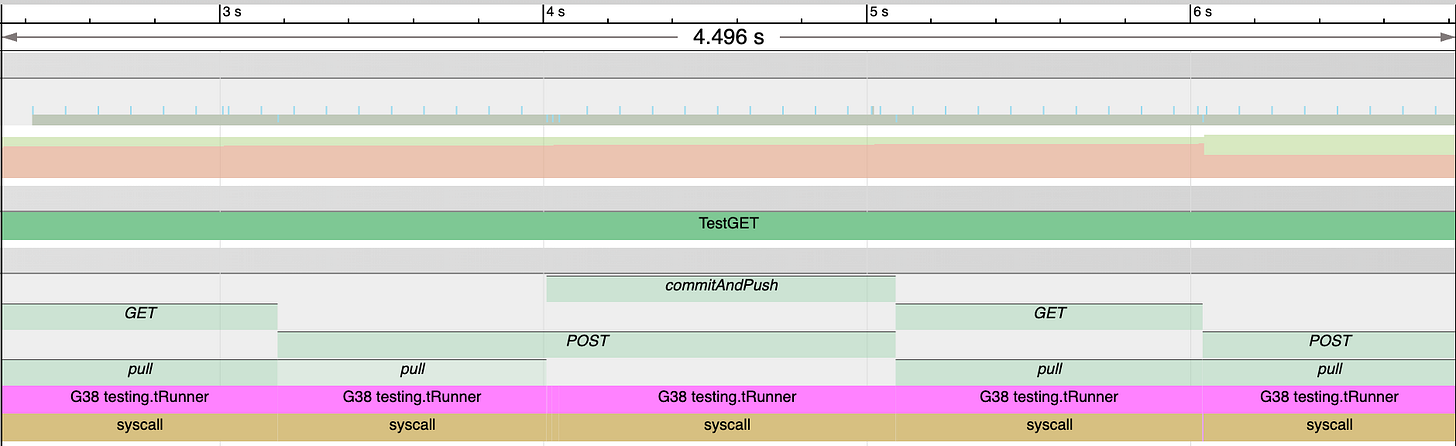

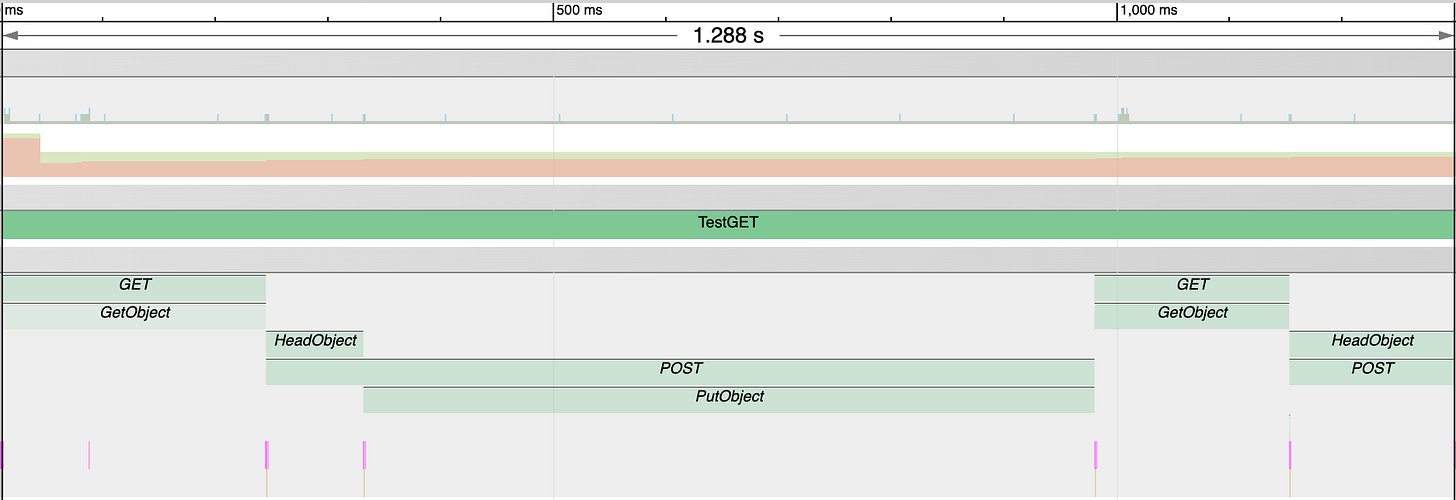

For comparison, I added tasks and regions for runtime traces and loaded example trace files with go tool trace. Screenshots of the relevant segments of these traces are below, with Git first:

From this quick example, we’re seeing the object storage backend being about 4x faster than the Git backend (not including the intial clone). We also see the Git operations dominated by git pull, with each call taking ~800ms, compared to ~200ms for a GetObject call for object storage. Given that the bulk of the test with object storage is dominated by PutObject, you can imagine that a more read-heavy request breakdown would leave Git looking even worse off.

Next steps

Suffice to say, the naive Git CLI approach is slow as heck. There’s almost certainly some overhead that can be eliminated here. Each CLI call will need to create a new connection to the Git server, which could potentially be persisted. Complex pulls could also have a lot of work to do unpacking files into the local repo.

I’ll be using go-git to interact with Git at a lower level, at the plumbing, or maybe even the protocol itself. I might even get time to look at those concurrency issues. Keep your eyes peeled for part 2!

The pull-on-every-operation overhead is brutal but expected. What's interesting is that even the naive approach shows potential if you're willing to trade speed for built-in versioning and auditability. Those race conditions are going to be the real challenge though, especially if you're thinking about concurrent writes. Looking forward to seeing what happens when you drop down to the plumbing layer.