Note to future self: use trunk-based development

I've used trunk-based development for a good long while, and am willing to predict I'll continue to do so as long as I'm using Git.

This isn’t really a hot take. I’ve been using trunk-based development for about a decade now, and most of the times since that I’ve tried something else it went so poorly I switched right back.

To avoid wasting time in future, I’m leaving this post as a warning to myself just in case I “invent” a new branching strategy on some idle afternoon. Here be dragons.

What is trunk-based development?

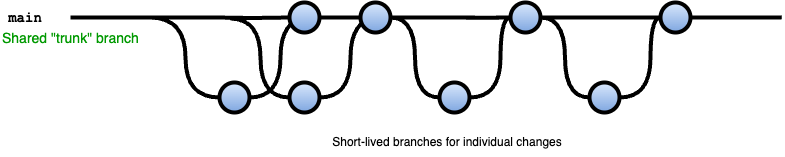

Trunk-based development is a branching strategy in which everyone commits their code to a shared branch. This is typically the default branch in a Git repo, the one you get automatically when running git clone.

Any additional branches are short-lived, on the order of days, containing small changes representing a single task for a single developer. Once a change is reviewed and approved, it is merged into the trunk.

By frequently merging, the complexity of any individual merge is greatly reduced. Having had to sift through large numbers of merge conflicts for a too-large change I can say this is nothing but a good thing.

Builds and releases are always cut from the trunk, which requires that each individual change leaves the codebase in a releasable state. This can seem like a chore at times, especially if you have a large number of automated tests to run. But it’s a discipline that pays off in the end, since the scope of each change is probably small enough for the author to quickly identify the cause of failing tests.

Keeping the trunk releasable also makes it easier to implement CI/CD practices, so you can deploy more frequently. More importantly, if something goes wrong, you can easily revert to the previous change and not sacrifice much in the way of functionality.

You may also hear of GitHub Flow, which is similar to trunk-based development, promoting small, but complete changes on branches, but with the understanding that GitHub’s PR model may require multiple commits in each branch.

What are the alternatives, and why are they terrible?

Git Flow

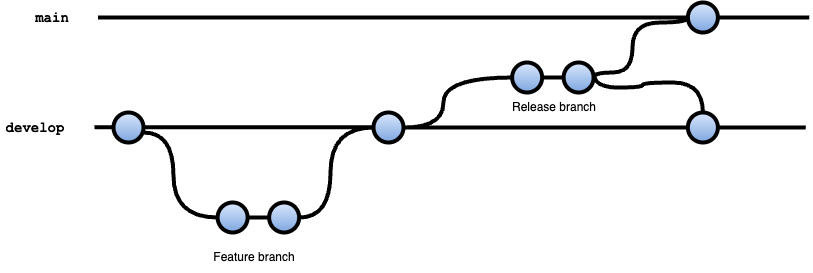

The most popular alternative - or at least the one I’ve heard people talk about most - is Git Flow. This model involves a main branch, but also develop, feature, release and hotfix branches.

Most work starts from the develop branch, with feature branches being created to bring new features to completion over multiple commits before being merged in. Once enough features have been developed to consider a release, a release branch is created. This release branch is tweaked as needed before merging into the main branch to be deployed, and also back into the develop branch to incorporate the extra changes.

The diagram above omits hotfix branches, which are created from main to quickly fix problems and then merged into both develop and main as with release branches.

You can argue that this keeps main in a releasable state for all the CI/CD goodness, but changes have to take a pretty arduous route to get there. Not only that, but the more work you pile into each branch, the more likely it is you’ll have to do even more work to merge them. Not only that, but you’ll be double-merging some of these branches - even more chores.

I tried a cut-down version of Git Flow for a few projects, maintaining a develop branch and merging directly from that into main. This highlighted another challenge for me, socializing to contributors which branch they should be working on. Unpicking a PR that was created from main instead of develop was not a fun bit of busy work.

The diagram was also a pain to draw.

Release branches

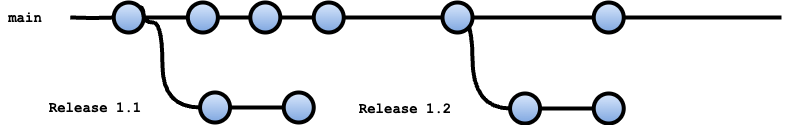

Rather than releasing from a single main branch, you could also create separate branches explicitly for the purposes of a release. Most feature work happens on the main branch, with branches being created for specific releases. This is sometimes also called GitLab Flow.

Early in my career, this was a model I used when working on “boxed” software. We’d be shipping discrete releases of our application to customers to install on their own hardware. The cost of sending out a patch was high, so there was a lot of pressure to get each release right before shipping. We’d hold frequent meetings to check for “ship stoppers” on each release.

The pursuit of release perfection created it’s own cleanup chores. As you might have noticed in the diagram above, improvements made directly to a release branch may or may not have been merged back into main. Sometimes we’d end up making the same fix multiple times to different releases in different ways.

There were some changes on the release branches we definitely didn’t want merged back, though. One of the last tasks on a release branch was to bump the version number in code and disable a ‘time bomb’ for pre-release code. One time we forgot to make the latter change and the resulting chaos made the news.

Branch per environment

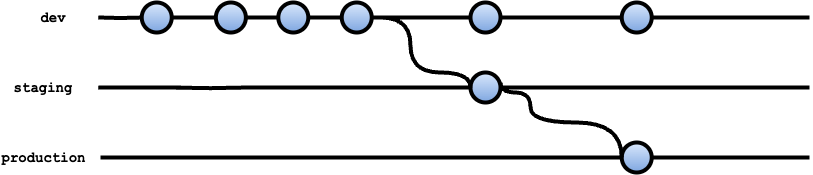

If you have sequential environments, like dev, staging and production, you may be tempted to have a separate branch for each.

The bulk of feature work would be done on the dev branch, and merged to staging once deemed ready. Similarly, if everything’s working in staging, you merge to production for release.

This might seem like a powerful way to control rollout of changes, and might even seem “GitOps-y”, but you either end up with a lot of manual work to perform the merges, or you have to automate merges - another layer of tooling to implement.

Unless you have really good branch protection in place, you’ll also run the risk of someone accidentally merging to the wrong branch, and having to come up with a procedure to undo that after a couple of subsequent merges go through.

Conclusion

So, future me, don’t be tempted by the allure of alternative branching models. You’ll safe yourself a lot of headaches by sticking with trunk-based development.

And let me know if you ever get better at drawing diagrams.